The Real Bottleneck: Why Energy, Not Ambition, Is Stalling the Asia-Pacific’s AI Data Center Boom

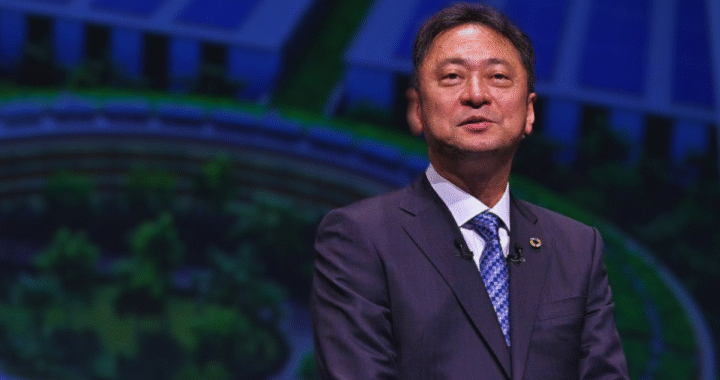

Princeton Digital Group leadership at the TY1 Campus ribbon‑cutting in April 2025. From left: PDG Managing Director Yoshinaga Takahashi, PDG Chairman, CEO, and Co-Founder Rangu Salgame, EXEO Group President and CEO Tetsuya Funabashi, Saitama City Economic Bureau Director of Economic Affairs Yoshihisa Kaneko, Saitama Prefectural Assembly Member Nobuaki Sekine.

The Asia-Pacific’s AI infrastructure boom is now being throttled by a less visible, slower-moving crisis: grid readiness. While billions continue to flow into land banking and hyperscale campuses, many are discovering that electrical capacity, not ambition or financing, is the biggest obstacle to operationalizing AI-ready facilities.

A Project Delayed Is a Region Warned

Tokyo offers a cautionary tale. Princeton Digital Group’s TY1 Campus opened in April 2025 after physical completion in 2024, only after relocating to Saitama due to grid congestion in central and eastern Tokyo. Meanwhile, the METI Strategic Policy Committee warned in June that electricity consumption from data centers and AI workloads could surge from ~14 TWh in 2018 to as much as 90 TWh by 2030, underscoring the depth of the bottleneck.

This is not an isolated case. In May 2025, Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) released a revised 2030 digital infrastructure roadmap that warned of a significant shortfall in data center–related grid capacity. Meanwhile, South Korea’s approvals for hyperscale campuses are imperiled by insufficient substation capacity and transformer procurement delays.

Capacity Crunch from Seoul to Singapore

Singapore, once considered a blueprint for data center policy, remains under a de facto moratorium. A new 300 MW tranche was announced in March 2025, but developers say competition for those permits has become a zero-sum game. Some projects have opted to expand into Johor or Batam, but that introduces new regulatory challenges and grid interconnectivity risks.

In India, the scale of AI training clusters has overwhelmed assumptions baked into utility planning. In April 2025, Maharashtra’s state power utility admitted it was under-equipped to support the additional 600 MW of capacity requested by foreign joint ventures in Navi Mumbai alone. Meanwhile, emerging markets across Southeast Asia are reporting similar utility coordination challenges.

Grid Modernization Is the Next Race

According to Structure Research, the Asia-Pacific region will require 13 additional gigawatts of capacity by 2030 to meet AI demand. But as grid lag sets in, the bottleneck is no longer capital or land, but a mismatch between digital infrastructure ambitions and national utility timelines.

Public-private grid development mechanisms such as Malaysia’s Green Electricity Tariff scheme and those contemplated in Japan’s 7th Strategic Energy Plan are beginning to emerge. However, most remain limited in scope or are not tailored for hyperscale loads.

The strategic question is no longer whether a market has demand or ambition. It is whether its power infrastructure can deliver on time, at scale, and with resiliency.

Saitama as a Sign of Things to Come

The TY1 Campus, despite its hurdles, now stands as a symbol of adaptability and strategic compromise. PDG’s leadership, alongside local officials and utility executives, framed the relocation to Saitama as a win for distributed digital development. But few in the industry miss the underlying point: even the best capitalized, best designed facilities are at the mercy of grid realities.

For data center CEOs, this is no longer a technical issue relegated to engineering teams. It is an executive-level, boardroom concern that shapes timelines, financing terms, and investor confidence.

As AI transforms global compute needs, it is time for the Asia-Pacific’s digital infrastructure community to tackle the region’s invisible bottleneck head-on: the grid.

Time to Market – Why Execution, Not Strategy, Is the Philippines’ Digital Pivot

Time to Market – Why Execution, Not Strategy, Is the Philippines’ Digital Pivot  Redefining the Grid – Why the Power System Is the New Data Center Frontier

Redefining the Grid – Why the Power System Is the New Data Center Frontier  Deal Architecture 2.0 – Execution Risk Outpacing Pure Capital Availability

Deal Architecture 2.0 – Execution Risk Outpacing Pure Capital Availability  Cross-Border Complexity – How Hyperscale Is Forcing Horizontal Integration

Cross-Border Complexity – How Hyperscale Is Forcing Horizontal Integration  Energy, Not Just Real Estate – Rethinking Data Campuses With Power in Mind

Energy, Not Just Real Estate – Rethinking Data Campuses With Power in Mind  SoftBank Bets on Green Future with Japan’s Largest AI Data Center in Hokkaido

SoftBank Bets on Green Future with Japan’s Largest AI Data Center in Hokkaido